ChatOps: A Brief History

If you’ve been in the DevOps space over the past few years, you’ve probably heard the term “ChatOps” thrown around. If not, there’s a simple definition:

ChatOps: Performing Operations tasks in group chat.

A good example of this would be kicking off a deployment to production by typing a command in a chat room.

There are plenty of videos and slidedecks of the power of this approach, but I’ll just include GitHub’s here:

GitHub popularized ChatOps by open-sourcing their chat bot, Hubot.

When I first saw this approach, I slowly grasped the benefits:

- You can use a natural language to interact with remote APIs to make it easier for anyone to perform commands.

- Performing these operations in a group chat room means that others learn about the available commands by watching you.

- Similarly,o perations are performed in the open, so that multiple Operations folks aren’t stepping on each others’ toes, and things aren’t fixed in secret.

Working with Hubot

I started playing around with Hubot, and there were already a wealth of plugins for things like interacting with Nagios, Jenkins, and GitHub.

However, I ran into a few issues when running plugins I downloaded or ones I scripted:

- There is no built-in authentication. Anyone can run anything. This is in part due to the level of trust that GitHub assumed when writing Hubot, but there are plenty of organizations where this wouldn’t fly. Sure, there’s the hubot-auth plugin, but you have to incorporate it into any plugin that needs it.

- Plugins are coded in CoffeeScript, which transcompiles into JavaScript. If you’re not familiar with either, it can be an uphill climb to learn how to write your own plugins.

- There’s no isolation when running plugins. I’ve had plenty of instances where a poorly-coded plugin (either by myself or someone else) crashed the whole Hubot daemon.

Introducting Cog

Apparently I wasn’t the only one with these concerns. Mark Imbriaco’s Operable created Cog as an answer to Hubot’s weaknessed in February of 2016.

Written with Elixir, Cog addresses Hubot’s issues by:

- Requiring authentication for all commands. Any bundle (Cog’s term for “plugin”) must explicitly list permissions for each command. It’s your standard role-based access control scheme: A User is a member of a Group; Roles are attached to Groups that allow specific Permissions.

- Using Docker to run all bundles. This means you can write your bundle in whatever language you choose. If you can put it in a container, Cog can run it. This also means that running a bundle is done in an isolated container, and should not affect any other bundles, or even the Cog daemon.

Cog’s philosophy

Mark Imbriaco gave a talk at Monitorama 2016 here in Portland, OR last year:

He described “humanscale systems”, or systems with APIs that help those in Operations learn and better understand the tools they interact with as part of their jobs. He did an interview with Operable that further expands on this topic, and spoke about why Cog is an attempt to build that approach into group chat.

Getting started with Cog

The Cog Book is a great resource for getting up and running with Cog. It includes a Docker Compose file that has everything built in.

It also includes instructions on writing your own bundles. There aren’t too many official bundles out there yet, so you may find you’ll need to write one yourself.

Since I have a lot of home automation and tasks built into my personal Rundeck

server, I wrote a really quick bundle in Go as a wrapper around John Vincent’s

excellent library for the Rundeck API, go-rundeck.

It wasn’t too difficult, and Cog’s config.yaml file for defining a bundle’s

commands makes it easy to document everything. My first attempt is available

in the Cog Warehouse here. I’ve only created a few

commands so far, and I plan on revisiting it to flesh out commands for most of

the Rundeck API.

Chatting with Cog

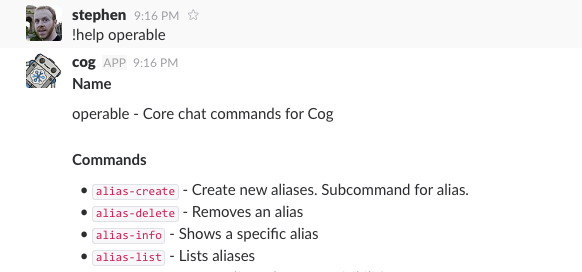

Interacting with Cog in a group chat room is done by either mentioning it by

name (e.g., @cog), or by using a prefix, which defaults to !. You can list

help:

If your command is provided by a specific bundle, you run it with:

!<bundle-name>:<command> <arguments>

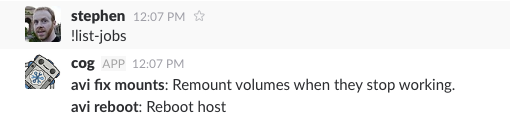

But if your command is unique to the bundle, you can omit the name. Here’s me

running rundeck:list-jobs to list jobs from my default project:

When writing a bundle, you can control its output with templates to make it more readable, but leave the default output in a machine-readable format like JSON to pipe it to a separate command.

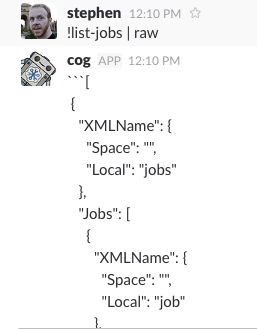

Say you want specific information from a command, but you don’t know what its

JSON output looks like. you can pipe it to the built-in raw command like so:

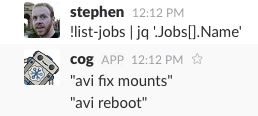

Knowing that, you could pipe it to the jq command (from the jq bundle) to get just a list of job names:

Looks a lot like a Unix command line, right? That’s no accident. Operations folks familiar with the command line tools available in a shell like Bash should have no problem picking these up.

Cog’s future

Since releasing version 1.0 of Cog, Operable has since shut down. However, the former employees have committed to keep development going. They also have a few large companies that are using it in production. Additionally, it’s all open source, so anyone can contribute.

I think Cog’s future is important, and I’m definitely interested in keeping it going. Writing bundles wasn’t too difficult for me, so I’m definitely looking at adding more in the future.

Links

- Cog source: https://github.com/operable/cog

- My Rundeck bundle source: https://github.com/steeef/cog-go-rundeck